From the very beginning of cinema, filmmakers have wrestled with the question of how to make the unreal appear real. In the early silent films, directors relied on simple props and trick editing to create illusions that startled audiences unused to moving pictures.

From painted backdrops to double exposures to conjure ghosts and magic, people were experimenting on things to what would eventually become Hollywood. By the mid-20th century, practical effects had matured into a sophisticated craft. Monster suits, prosthetics, squibs for gunshots, and gallons of fake blood were staples of horror and war films alike.

Audiences could be thrilled, even disgusted, but they knew what they were watching was part of the artifice of cinema.

Then came a new narrative form called the mockumentary, or fiction filmed as if it were nonfiction. Documentaries had long carried the weight of authority, presented as objective truth. To wrap a fictional story inside that style was disorienting. It stripped away the distancing polish of traditional cinema and put viewers into something that felt disturbingly authentic.

For the most part, audiences were not ready for that shift.

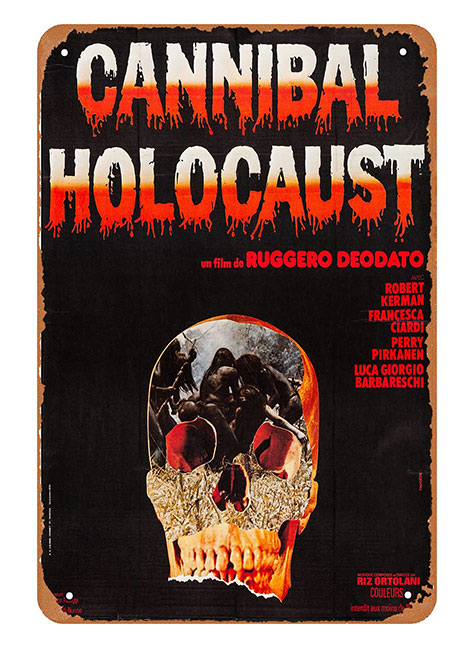

And Cannibal Holocaust, which arrived in 1980, was the turning point of that.

It's also a film that survived the test of time, even after the internet decades later, with newer generations contributing to debating its horror.

When it was first released, the world was confronted with a film that shattered boundaries.

Director Ruggero Deodato framed the movie as recovered footage from a missing documentary crew, lending it a grim realism that unsettled in ways few films ever had. The violence was relentless, but what made it uniquely horrifying was the way it blurred fact and fiction. The acting was raw, the shaky camera uncomfortably close, the jungle setting unforgiving.

Rumors spread almost immediately that the atrocities depicted, from torture to the rapes and the killings, were not staged at all.

The inclusion of genuine animal cruelty only fueled that belief.

Authorities took the rumors so seriously that Deodato himself was briefly arrested and forced to prove that his actors were alive and unharmed.

The film begins with an anthropologist, Professor Harold Monroe, being recruited to investigate the disappearance of a young American documentary crew who vanished in the Amazon while filming indigenous tribes.

Monroe travels deep into the jungle, first encountering a series of hostile and mysterious tribes.

With the help of locals, he eventually makes contact with the Yanomamo, one of the tribes the crew had been studying, and after tense negotiations he recovers the cans of film shot by the missing documentarians. The footage is then brought back to New York for review.

The recovered film becomes the centerpiece of the story.

It follows four young filmmakers: Alan Yates, his girlfriend Faye Daniels, and their two colleagues, Jack Anders and Mark Tomaso. Initially, their footage shows them trekking into the Amazon, apparently with a noble intention of documenting “primitive” tribes. But soon, their behavior reveals itself to be manipulative and exploitative.

They stage confrontations for dramatic effect, burning down a village hut to make it look as though the tribes are victims of rival attacks, while laughing about it behind the camera. They coerce, mock, and brutalize the people they claim to be studying. At one point, they capture a young girl from a tribe, tie her up, and Alan rapes her, with Faye, angry, passively watching. Later, the men gang-rape a tribal woman, further eroding any illusion of objectivity or compassion in their project.

The film intercuts moments of shocking real animal slaughter. In one scene, the crew hacks apart a turtle, pulling it from its shell and dismembering it while it’s still moving. In another, a monkey is decapitated. These sequences are genuine, with no special effects, and remain among the most notorious aspects of the movie.

As the crew grows more reckless, the violence escalates. They orchestrate a fake execution by forcing a tribe to impale one of their own, filming it for sensationalist shock value. In another sequence, they shoot and kill a pig for effect. Their disregard for human life and suffering becomes undeniable.

Eventually, the tables turn.

After burning down a Yanomamo village and killing several tribespeople, the documentarians are captured. What follows is brutal revenge. Jack is speared, Mark is castrated and killed, Alan is beaten to death, and Faye is sexually assaulted and finally killed after being forced to watch her companions die. The final moments of the footage depict the tribesmen dismembering and consuming the crew’s bodies, completing the cycle of exploitation and retribution.

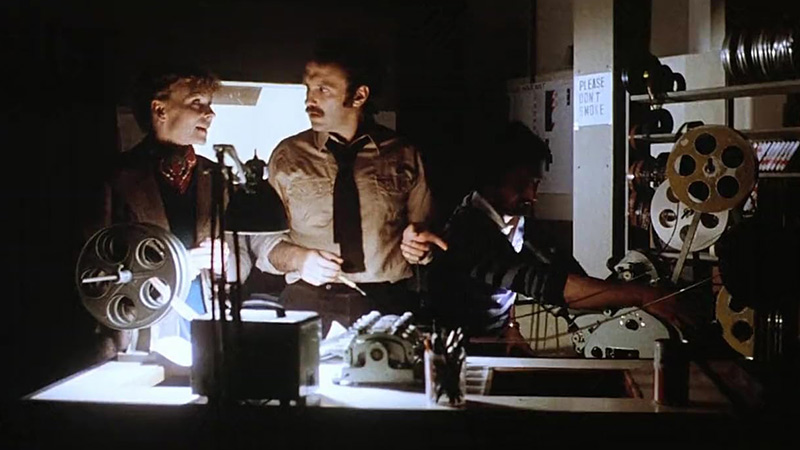

Back in New York, the television executives reviewing the footage are initially excited, calling it shocking and sensational enough to broadcast.

But as they watch to the bitter end, their enthusiasm turns to disgust. Monroe, shaken by what he has seen, convinces them to destroy the tapes.

The film closes with him walking out into the city streets, reflecting grimly on who the real cannibals are, the so-called savages in the jungle, or the modern world that exploits suffering for entertainment.

Cannibal Holocaust gained its shocking reputation not just from the way it was framed as found footage, but also because of how the filmmakers blended real brutality with clever practical effects.

The most infamous scene is the impalement, where a native woman appears to be skewered through her anus with a pole emerging from her mouth. In reality, the actress was seated on a hidden bicycle seat while holding a short piece of balsa wood between her teeth, and the camera angle sold the illusion of one continuous spike.

Other moments, however, involved no illusion at all.

The notorious turtle sequence shows the crew dragging a large turtle ashore, hacking off its limbs, and tearing it apart while it’s still moving. That animal was real, and its death was captured on camera. The same is true for the monkey beheadings, which were filmed twice due to camera issues, resulting in two monkeys being killed, and for the pig that was shot at close range.

These sequences remain some of the most controversial in film history, because the animal cruelty was genuine and impossible to disguise as movie magic.

The staged violence against humans, on the other hand, relied on prosthetics, squibs, and old-fashioned special effects.

Spears were retractable or angled so they appeared to pierce bodies, blood packs were hidden under clothes, and prosthetic limbs were designed to burst apart convincingly. For the castration and dismemberments, animal internal organs were packed into fake torsos and limbs, so when they were torn open, convincing gore can be seen.

And as for the tribesmen eating the filmmakers’ remains were actually tearing into piles of raw animal meat, dressed with fake blood and prosthetics to resemble human flesh.

Blood effects combined both traditional stage blood mixtures and, in some cases, animal blood to achieve a thicker, more convincing look. The syrup-based fake blood was applied heavily so it would cling to skin and shine under the camera, while squibs created bursts during violent impacts. The combination of sticky, glossy fake blood with raw animal organs made the eviscerations and cannibalism sequences appear disturbingly authentic, especially when shot through shaky handheld cameras that obscured imperfections.

Even the sexual assault scenes, though simulated, felt raw because of the handheld camerawork and the intensity of the performances.

In other words, camera works and practical effects, as well as real bloodied animal parts, blurred the line between artifice and reality.

Ultimately, Cannibal Holocaust worked as it did because of its unsettling mixture: staged atrocities that relied on prosthetics and clever angles, genuine killings of animals that shocked even seasoned viewers, and an unpolished documentary style that made everything appear like unfiltered evidence.

This combination of fake and real convinced audiences, censors, and even police that they were watching death itself, a reaction no other horror film had quite managed before.

The backlash was immense.

Bans swept across countries, critics denounced it, and for years the film lingered in obscurity, passed around like forbidden contraband.

Because some of the scenes were so convincing, Deodato even had to bring the actress who was impaled in the film into court to prove she was alive. This happened because Deodato had told the actors and the actresses of the films to go off the grid, in order to make things convincing, a decision that worked.

But as the internet matured, so too did the legend of Cannibal Holocaust.

Forums, torrent sites, and horror communities resurrected it as a “rite of passage,” the kind of movie you dared your friends to watch if they claimed they could stomach anything.

YouTube video essays and Reddit discussions keep its reputation alive, decades after the film's release. Even to modern visual effects standards, and subsequent mockumentaries and found footage films that were introduced after Cannibal Holocaust, seem pale. The internet always framed footage with the same warning: this is not just another horror film, this is the one that broke the rules.

Cannibal Holocaust remains a divisive artifact.

To some, it is a grotesque exploitation piece that should have never been made.

To others, it is a brutal but fascinating experiment, the forefather of found-footage horror that would later inspire mainstream hits like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity. Either way, it is a reminder of the fragile line between illusion and reality in cinema, and how powerful the medium becomes when that line is crossed.