The choice between a dedicated camera and a high-end smartphone often boils down to a trade-off between image quality and convenience.

Dedicated cameras like DSLRs and mirrorless systems feature much larger sensors, enabling superior low-light performance, less noise, and broader dynamic range. Their ability to use specialized lenses—whether for sweeping landscapes, far-off subjects, or rich background blur (bokeh)—gives photographers immense creative control.

With tactile, manual controls and ergonomic designs, they remain the go-to for professionals and serious enthusiasts.

Smartphones, meanwhile, have transformed photography with unmatched portability and powerful computational photography. Always there, always connected, they’re perfect for capturing spontaneous moments and instantly sharing them. But despite clever software tricks, smartphones still suffer from smaller sensors, digital zoom limitations, and simulated effects that can’t quite match optical quality.

Recognizing this gap, Adobe introduced 'Project Indigo'—an ambitious effort to bring DSLR-level performance and control to smartphone photography, without sacrificing the convenience of mobile shooting.

Adobe Labs releases an experimental digital photography app Project Indigo (https://t.co/5KbUXV0n3q) to showcase breakthrough innovations, including reflection removal, which is being published at CVPR this week. Check out this blog: https://t.co/cna9MaJdUd pic.twitter.com/reEstd4Mfj

— Adobe Research (@AdobeResearch) June 13, 2025

In an era where the smartphone has become the de facto camera for millions, Adobe's release of Project Indigo marks a significant, if somewhat expected, entry into computational photography.

Initially available as a free app for iPhones, Indigo offers a blend of advanced image stacking, manual control, and a philosophy rooted in realism—rather than over-processed output. It arrives at a time when the line between casual mobile photography and serious imaging continues to blur.

Project Indigo is spearheaded by Marc Levoy—best known for leading computational photography at Google for the Pixel—and Florian Kainz, an imaging researcher with a history in high-end visual fidelity. This isn’t Adobe’s first foray into mobile imaging (Lightroom Mobile has long offered a camera mode), but Indigo is different in both structure and intent.

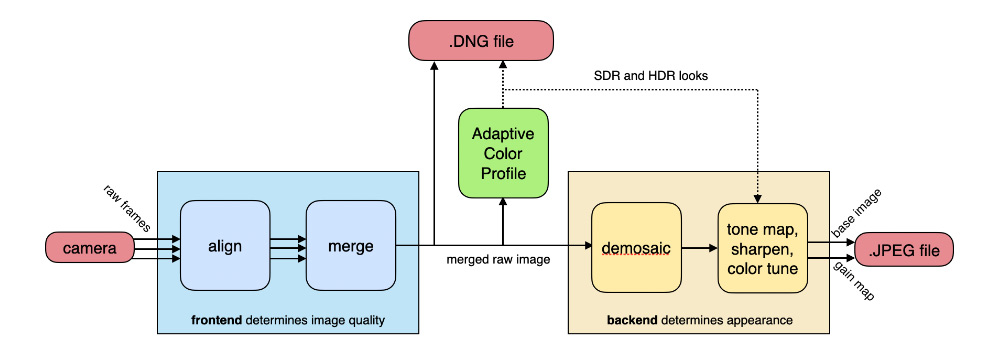

What sets Indigo apart is its use of multi-frame image stacking as a default, not an optional feature.

When users press the shutter in Indigo’s Photo mode, the app will not capture a single image. Instead, the app has already been buffering a short burst of raw frames behind the scenes. When triggered, it selects, aligns, and merges up to 32 of them, resulting in an image with significantly less noise, better highlight retention, and improved dynamic range.

This method isn’t new—it’s been used in astrophotography and other low-light disciplines—but Indigo brings it to the casual user without much friction.

Then, it has a Night mode, in which Indigo switches to a longer exposure process that requires a steadier hand—or ideally, a tripod. The app guides users with an on-screen indicator to help ensure frames align properly during this longer capture. The result is sharper low-light images without excessive noise reduction, which often smears textures in conventional smartphone images.

As for the manual control, it offers sliders for ISO, shutter speed, focus, white balance, and even the number of frames per burst.

Unlike the stock iOS camera, which hides much of its computation and applies aggressive post-processing, Indigo leans toward transparency. It gives users RAW output in 16-bit DNG format or JPEGs with HDR-compatible gain maps. This matters because the JPEG output is optimized for viewing on HDR-capable devices while still looking natural on SDR screens—something not all mobile apps handle well.

Indigo also avoids the highly processed look that plagues many smartphone shots. Instead of artificial sharpening and saturation boosts, Adobe has embedded what it calls “Adaptive Color”—a color processing pipeline that adjusts tonal profiles based on contextual scene understanding. The result is subtle, even bland to some eyes, but far more suitable for post-processing or print workflows.

Another feature worth mentioning is multi-frame super-resolution, available when zooming in. This technique uses slight hand movements between frames—natural human tremor—to simulate a higher-resolution capture. It’s a smart solution to the inherent limitations of smartphone zoom, which is mostly digital and degrades image quality quickly. In tests, the resulting zoomed images offer noticeable sharpness gains over standard crop-zooming.

Despite these strengths, Indigo isn’t without constraints.

First, it's exclusive to iOS—and even there, it only supports iPhone 12 Pro and newer models. Some features like HDR JPEG output, real-time previewing, and super-resolution zoom require even newer hardware, particularly from the iPhone 14 Pro and iPhone 15 Pro lines. Users of older models won’t see the full benefit, which limits its potential reach for now.

Another consideration is that Indigo is currently a standalone app, not deeply integrated into the broader Adobe ecosystem—yet.

It does allow for export into Lightroom and other Adobe tools, but there's no full sync or editing suite baked into the app itself. This may frustrate users expecting an all-in-one solution. The app's design seems more exploratory than polished in that regard—likely by design, given its “Project” label and its presence in Adobe Research rather than Creative Cloud.

Indigo also includes something called Technology Previews—experimental features in development. One example is a reflection removal tool, which uses semantic understanding to isolate and eliminate reflections in glass surfaces. This feature isn’t final, and Adobe makes no promises about its stability or availability in the future. But it’s a clear signal that the company sees Indigo as a sandbox for future tools that may migrate to Lightroom, Photoshop, or even their AI imaging platforms.

To Adobe’s credit, there’s no login wall. The app is free and functional out of the box, which is refreshing in a landscape filled with subscription traps and locked features. Whether that continues as the app evolves remains to be seen.

Indigo is not meant to replace the stock camera app or replicate Instagram filters—it’s positioned more like a research experiment for photographers who value both control and fidelity.

Whereas apps like iPhone stock app, or apps like Snapseed create more saturated, high-contrast outputs, Indigo targets a narrower audience: mobile photography enthusiasts, Lightroom users, and perhaps DSLR veterans looking to simplify their gear without giving up control.

It’s a niche, but a meaningful one, especially as smartphones continue eating into the territory of entry-level cameras.