Business is business, and business knows no boundaries. It's only to conquer or be conquered.

Some businesses would sell their souls for just a fraction of an edge—cutting corners, bending ethics, even trampling over privacy. In the ruthless race for profit, some don’t just blur the lines—they redraw them to suit their needs. From shady data harvesting to deceptive marketing, it's all part of the game to dominate markets, control narratives, and lock users into ecosystems.

This is what exactly happens in Meta (formerly Facebook) and Russian tech giant Yandex.

An investigation by researchers from Radboud University and IMDEA Networks has unveiled that Meta and Yandex have been employing covert techniques to de-anonymize Android users' web browsing activities.

This method operates even when users are in Incognito Mode or utilizing VPNs, effectively bypassing standard privacy protections.At the heart of the discovery lies a quiet yet powerful mechanism—embedded analytics scripts like Meta Pixel and Yandex Metrica, which are widely used by millions of websites to track visitor behavior and measure advertising performance.

But beneath the surface, these scripts were doing something more: leveraging a loophole in Android’s core networking behavior that few users—and frankly, few developers—realized could be turned into a surveillance tool.

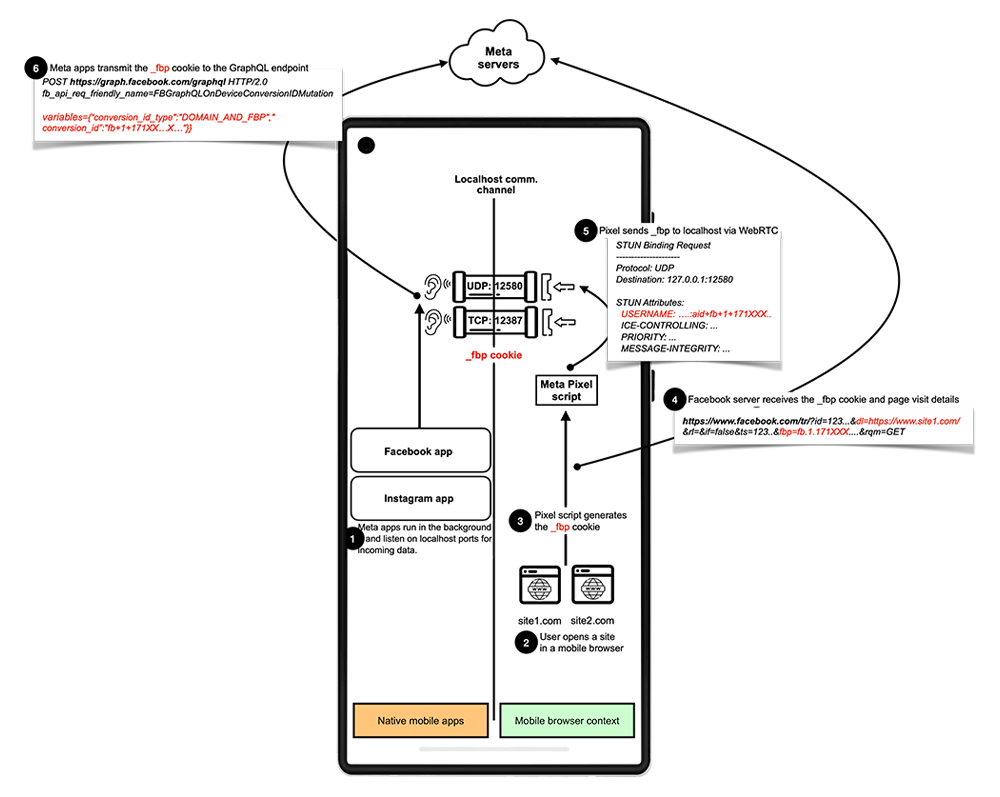

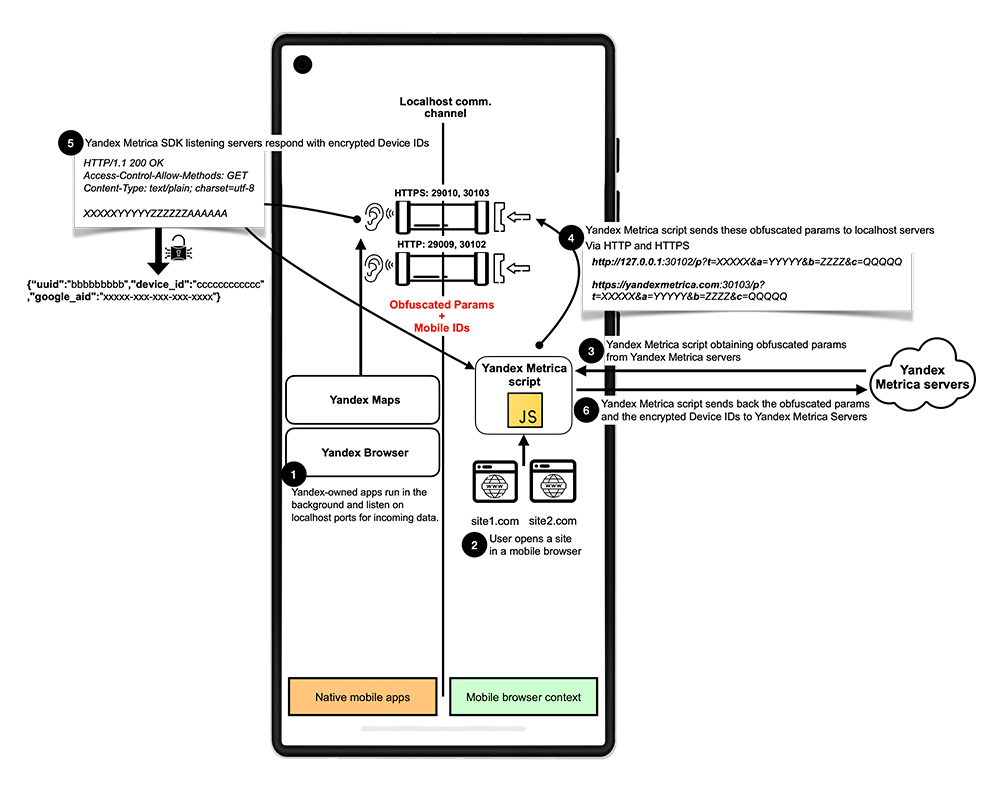

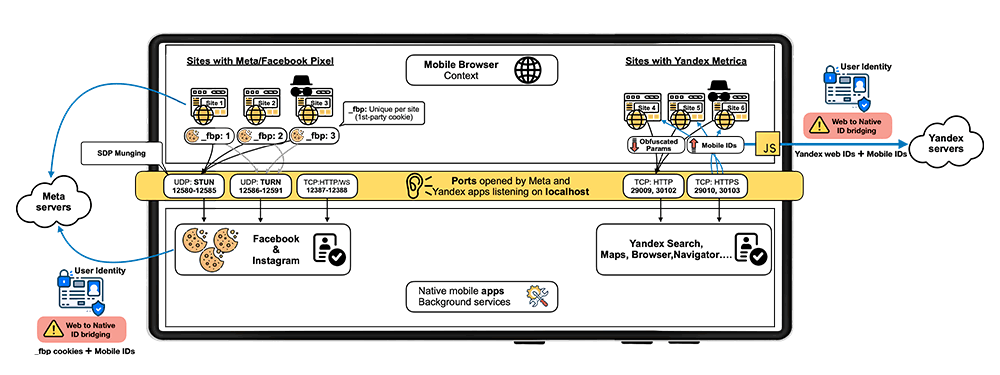

Modern mobile browsers, especially on Android, include support for local communication protocols that enable a wide range of legitimate features. From WebRTC-based video calls to file transfers and debugging tools, these protocols let the browser send HTTP requests to local ports (like those on 127.0.0.1, the loopback interface) to talk directly to native apps running on the same device.

According to a detailed research page on GitHub, that’s where things went sideways.

The Android operating system permits any app with basic internet access to open a listening socket on the loopback interface. Once that socket is open, any browser on the same device—without any explicit user permission—can send and receive data through it.

Here’s how Meta and Yandex turned that into a stealthy tracking mechanism:

- A user opens a website in their mobile browser (say, Chrome or Firefox).

- That website contains embedded tracking scripts—Meta Pixel or Yandex Metrica.

- These scripts initiate connections to localhost ports opened by native apps already installed on the device (e.g., Facebook or Yandex).

- The app responds, sending user identifiers—including session tokens, cookies, and device-specific data—back to the browser.

- The browser then shares this data with the tracking scripts, allowing Meta or Yandex to associate the anonymous web activity with the real user identity from the app.

This loopback-based communication allowed the companies to reconstruct users’ browsing behavior in detail—even after users had cleared cookies or enabled private browsing modes.

The script then forwards this data back to its parent service (Meta or Yandex), effectively linking the user’s browsing session with their app identity.

This form of inter-process communication, routed entirely through localhost, bypasses browser-level privacy tools like cookie deletion, tracking prevention, incognito mode, and even VPN obfuscation. It creates a backchannel between the web and the app—invisible to the user.

At the time of discovery, the scale was immense:

Meta Pixel was embedded in over 5.8 million websites worldwide. Yandex Metrica appeared on roughly 3 million websites.

That means millions of Android users were potentially exposed, even if they believed they were browsing privately.

"One of the fundamental security principles that exists in the web, as well as the mobile system, is called sandboxing," Narseo Vallina-Rodriguez, one of the researchers behind the discovery, said in an interview.

"You run everything in a sandbox, and there is no interaction within different elements running on it. What this attack vector allows is to break the sandbox that exists between the mobile context and the web context. The channel that exists allowed the Android system to communicate what happens in the browser with the identity running in the mobile app."

The research only found that the Meta Pixel and Yandex Metrica only target Android users.

While the researchers said that it's technically possible to target iOS because browsers on that platform allow developers to programmatically establish localhost connections that apps can monitor on local ports, exploiting Android is far more worthy.

Android imposes fewer controls on local host communications and background executions of mobile apps, the researchers said, while also implementing stricter controls in app store vetting processes to limit such abuses.

This overly permissive design allows Meta Pixel and Yandex Metrica to send web requests with web tracking identifiers to specific local ports that are continuously monitored by the Facebook, Instagram, and Yandex apps. These apps can then link pseudonymous web identities with actual user identities, even in private browsing modes, effectively de-anonymizing users’ browsing habits on sites containing these trackers.

Following the public disclosure of these practices, Meta ceased using this tracking method on June 3, 2025.

Browser developers, including Google and Mozilla, have initiated investigations and are developing measures to mitigate such privacy invasions. Google acknowledged that the behavior violates their security and privacy principles and has implemented changes to address the issue. Mozilla is also working on protections for Firefox users on Android.

The revelation has sparked significant concern among privacy advocates and users alike.

The ability of apps to circumvent established privacy measures underscores the need for stricter enforcement of platform policies and potential OS-level changes to prevent such abuses. As the digital landscape evolves, ensuring user privacy remains a paramount challenge requiring ongoing vigilance and adaptation.

What’s especially concerning about this technique is how it undermines user agency. Most users assume that incognito mode, VPNs, or even wiping cookies provides a fresh browsing session. But with loopback tracking, that assumption collapses—because the identifier never left the device in the first place.

What makes it even worrisome, the tracking method runs locally, hidden, requires no third-party cookie, evades browser-level privacy controls, and works even when users try to remain anonymous with all means offered.

This case underscores a broader issue in the privacy landscape: apps and platforms can exploit subtle OS behaviors in ways that users, and even regulators, rarely anticipate.

With tracking technologies becoming ever more creative—and invasive—it's a reminder that protecting user privacy isn't just about cookies anymore. It's about redesigning the architecture of mobile platforms to assume that every feature can be abused if left unguarded.

Takeaway: If you’re an Android user, no amount of private browsing or VPN magic can stop apps on your device from sharing your identity in the background—unless the platform itself closes the door.