The world is always moving, and so do people's views.

Not so long ago, having phone calls recorded by a third party was considered a eavesdropping. It was considered a scandal waiting to erupt, the things that populate tabloid headlines, government leaks, and corporate whistleblowing. Journalists hacking voicemails, intelligence agencies secretly running surveillance programs, companies caught eavesdropping on private conversations.

All that is fueled by a common cultural understanding that call recording was synonymous with secrecy, violation, and outrage.

In the age of AI, it loomed as one of the most unsettling scenarios imaginable.

Fast forward to today, and the story has flipped in a way that almost defies belief.

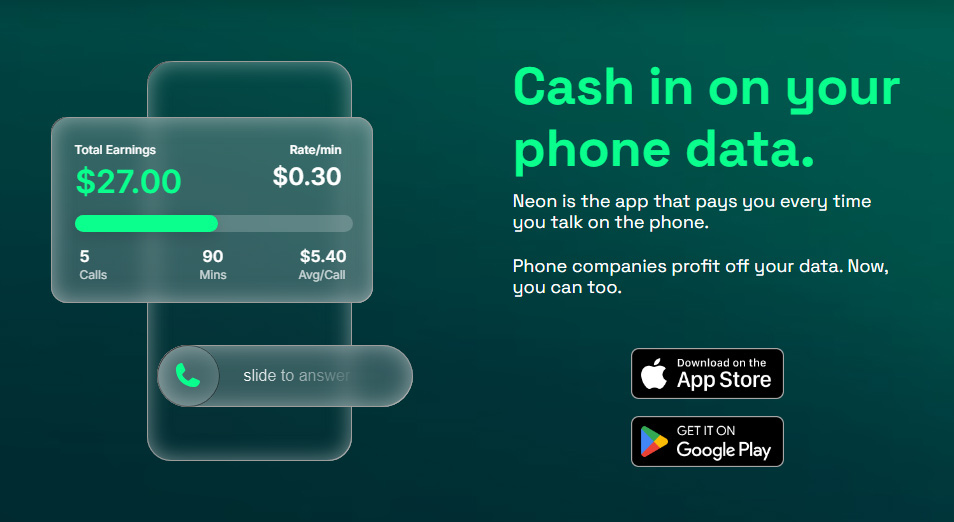

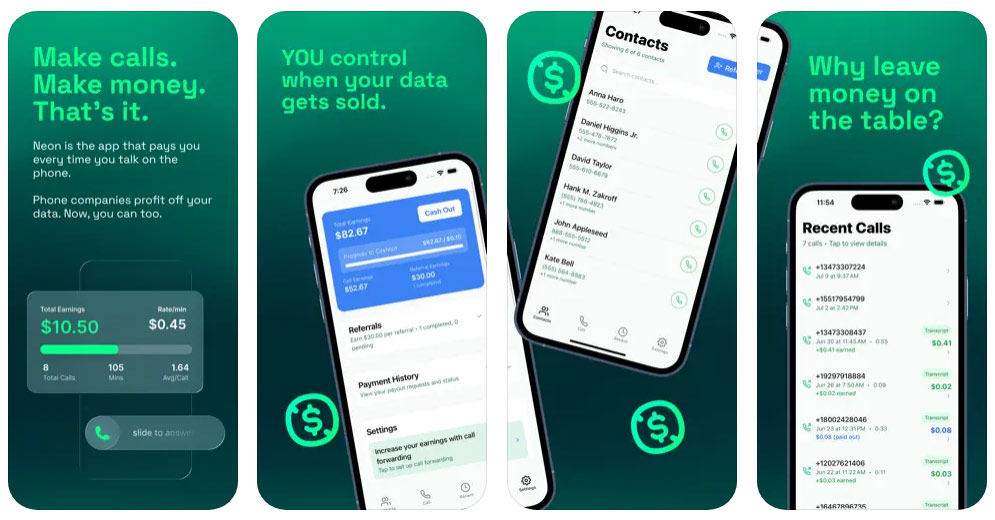

A new app called 'Neon' has surged to the top of Apple’s App Store charts, at one point outranking TikTok, Temu, and even Google. Its premise is simple, yet provocative: pay people to record their phone calls, hand over the audio, and sell it to AI companies hungry for data.

What was once treated as an invasion of privacy has now been packaged as a business opportunity.

For younger users facing rising costs of living, the allure is obvious.

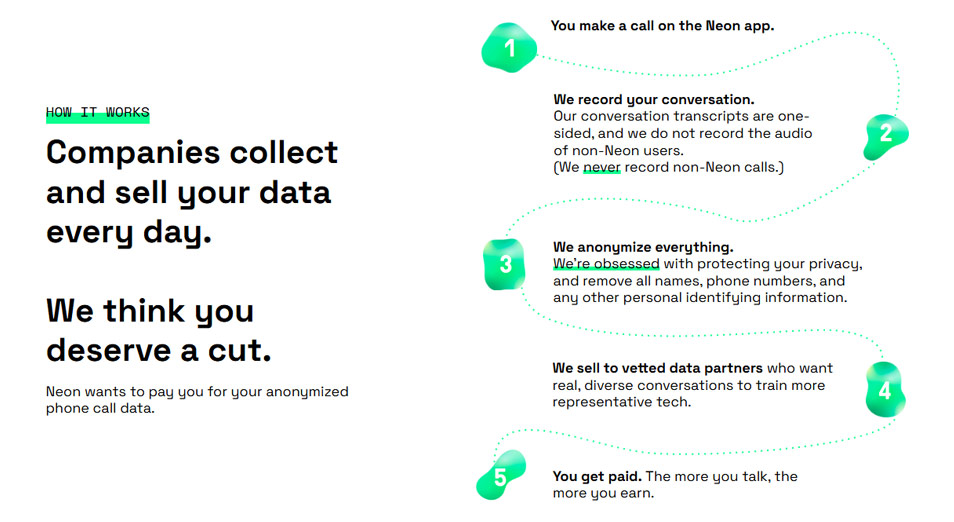

The app promises up to $30 a day, with per-minute payouts depending on whether the call is to a Neon user or not, and even offers referral bonuses. The pitch reframes surveillance as empowerment: users are not being spied on, and that it has made things clear in its privacy policy that Neon users will have their conversations recorded, to then be sold to some AI companies.

"We may disclose any information we receive to our current or future affiliates [...] " the policy says.

In other words, using Neon is no longer a passive surrender of data but an active exchange, wrapped neatly into the booming gig economy.

After all, in this modern world and society, people can rent their spare bedroom online, sell secondhand clothes through e-commerce, or deliver food ordered online for extra cash. So why not monetize conversations too?

Behind the shiny promise of easy money lies a more complicated reality.

Users aren’t just selling their time or old belongings: they’re selling their voices, their thoughts, their most private exchanges.

For AI firms, this is a goldmine.

Large language models and conversational AI thrive on authentic, messy, real-world conversations. Scripted data only goes so far. What companies want are interruptions, filler words, emotional inflections, the raw texture of human communication.

Neon provides exactly that, at scale, and it does so openly in a way that would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

But with that opportunity come deep concerns.

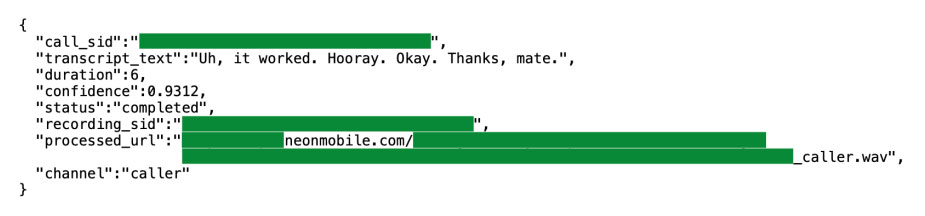

Neon insists it only records one side of a call, which is the caller’s, to avoid violating wiretap laws in states that require all-party consent. Still, the legal tightrope is shaky, and the company’s terms of service grant it sweeping rights to the recordings, from modifying and reproducing them to sublicensing them across media channels.

Even if the data is stripped of names and numbers, AI can infer more than users might realize. Voiceprints could be used to impersonate someone, generate deepfakes, or simply expose information in ways the user never intended.

The cultural shift is just as significant as the legal one. Where privacy was once a right to be defended, it’s increasingly treated as a commodity to be traded.

Younger generations, raised in a world where posting personal updates, livestreams, and photos online is second nature, see less of a boundary between private and public life. F

or them, selling call data feels like just another extension of the digital economy.

Older generations, who remember the scandal of phone hacking era, may squirm at the thought, but even skeptics can see the appeal of “getting paid for what’s already happening anyway.”

That fragile balance collapsed almost as quickly as it rose.

Within days of its viral success, Neon was forced offline after a devastating security flaw exposed exactly what users had entrusted it with.

According to a finding by TechCrunch, Neon’s servers weren’t properly restricting access. With basic tools, they could pull not only their own call transcripts and recordings but also those of other users. Information also include phone numbers, metadata, and payout details.

Thousands of private conversations, sold under the promise of empowerment, were suddenly vulnerable to anyone who knew where to look.

Neon’s founder, Alex Kiam, quickly pulled the app down, sending out an email blaming the pause on “adding extra layers of security” but omitting any mention of the data exposure.

The rise and the controversy of Neon in such a short span underscores how much the society's attitudes toward privacy have changed, and how far AI’s demand for data has stretched the boundaries of what people are willing to share.

On one hand, the app tapped into a powerful new model, letting individuals profit directly from their own information. On the other, it revealed how fragile that trust is, and how easily it can collapse when mishandled.

What used to be a scandal is now a side hustle, but the risks are bigger than ever. In the age of AI, the question isn’t just what we’re willing to give up. It’s whether we can afford the consequences when we do.