Humanity has long grappled with the challenge of long-term data preservation in an era where digital information explodes while traditional storage media, like hard drives, tapes, and flash, degrade over decades, succumbing to bit rot, environmental wear, or mechanical failure.

Microsoft has a solution for this, and it calls it the 'Project Silica.'

It represents a long-running quest to solve one of the biggest headaches in the digital age: how to preserve vast amounts of data indefinitely without the constant energy drain, periodic migrations, and inevitable degradations. And the roots of the technology trace back to earlier scientific work on laser-encoded glass storage, notably research from the University of Southampton around 2014 and beyond, where femtosecond lasers were used to inscribe data into fused silica with remarkable density and durability.

Microsoft researchers recognized the potential for this to disrupt cloud archival storage and began building on those physics principles around 2017, integrating it into their broader exploration of future cloud infrastructure at the intersection of optics, materials science, and computer systems.

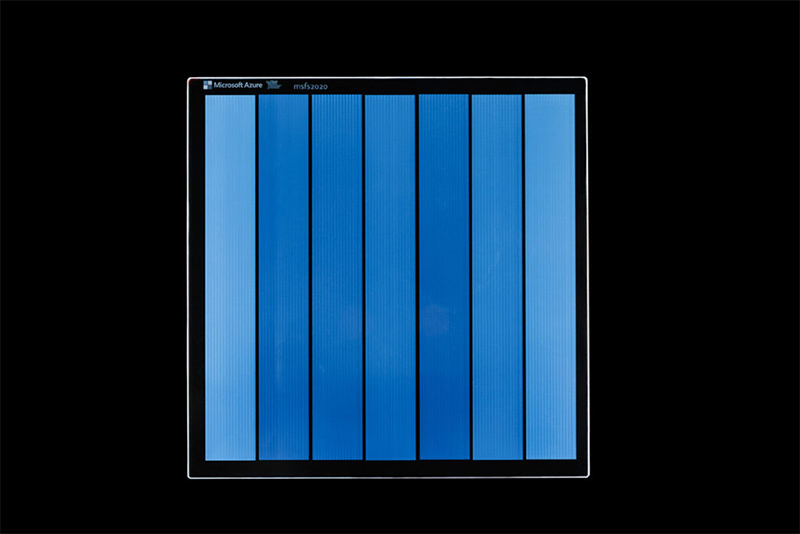

GitHub was one of the first that trialed this method back in 2020.

This time, Microsoft announced that it has made a major advancement to the project.

Project Silica originally etched data directly into silica-based glass using femtosecond lasers, creating a medium that could endure for millennia without power or maintenance.

In a significant step forward announced in February 2026, Microsoft researchers published groundbreaking findings in Nature, demonstrating that this technology no longer requires exotic, expensive fused silica but works effectively with everyday borosilicate glass, a kind of material commonly found in Pyrex cookware and oven doors.

The core innovation involves using ultra-short laser pulses to modify the glass's internal structure at a microscopic level, forming voxels, which can be described as three-dimensional pixels that encode binary data across hundreds of layers within a thin plate.

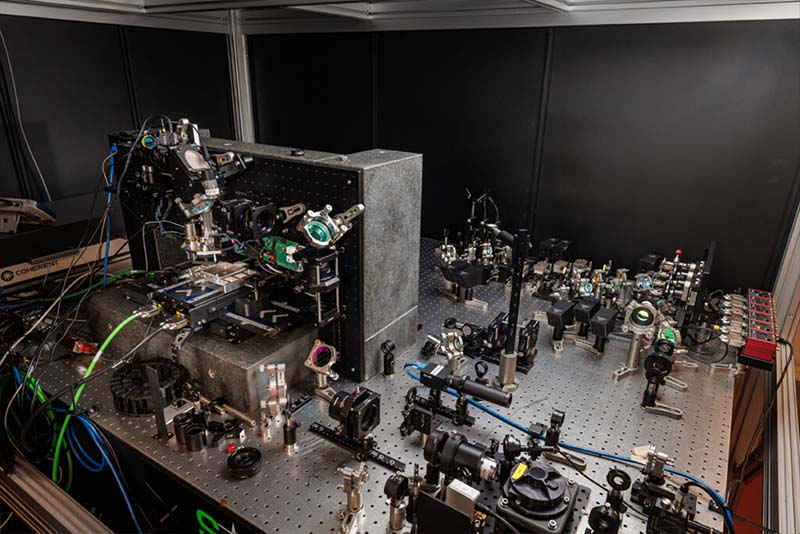

Previously, the process relied on birefringent voxels that altered the glass's polarization properties, demanding multiple laser pulses per voxel and complex multi-camera readout systems. But now, the advances introduce phase-based voxels, which require just a single laser pulse to change the material's phase, simplifying the writing process dramatically.

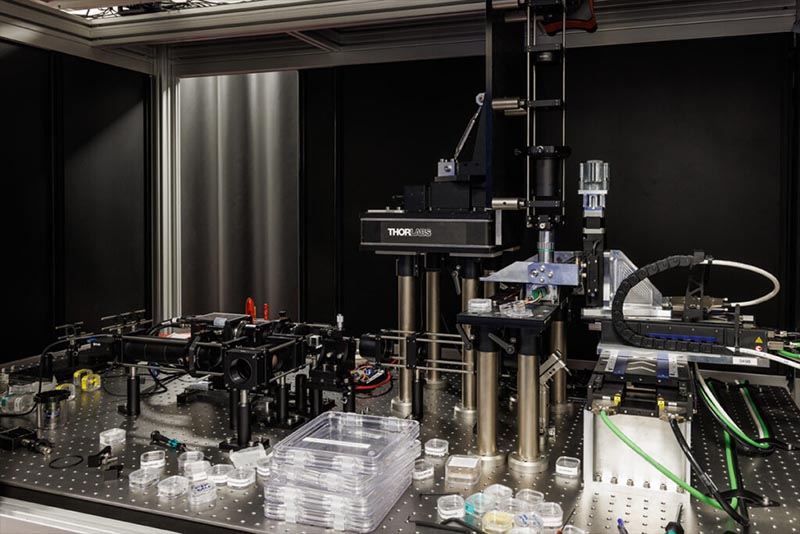

Reading has been streamlined too, now relying on a single camera to detect these changes, with machine learning algorithms compensating for potential interference in the densely packed 3D structure.

In demonstrations, researchers encoded up to 2.02 terabytes across 258 layers in a 2-millimeter-thick borosilicate plate measuring about 12 centimeters square. This is enough capacity to store vast archives like hundreds of thousands of photos or hours of high-definition video.

While this falls short of the 4.8 terabytes achieved in fused silica under optimized conditions, the trade-off brings major practical gains: write speeds reached between 18 and 66 megabits per second depending on the number of laser beams deployed, surpassing earlier fused silica performance in some configurations.

Parallel writing techniques, including beam splitting for pseudo-single-pulse operations, pave the way for even faster throughput with future multi-beam setups potentially exceeding a dozen beams simultaneously.

But what truly sets this approach apart is its durability.

Accelerated aging tests, combined with a new nondestructive optical evaluation method, project data integrity for at least 10,000 years at elevated temperatures, with longevity potentially stretching far longer under normal conditions.

This is possible because glass can withstands water, extreme heat, dust, scratching, and boiling. These are threats that doom magnetic tapes in decades or flash memory in warm environments. Unlike active storage systems requiring constant energy and periodic migration, Silica plates remain passive and immutable once written, making them ideal for cold archival storage where data is rarely accessed but must survive indefinitely.

The shift to abundant, low-cost borosilicate addresses a key commercialization barrier, reducing material expenses and simplifying manufacturing.

Microsoft has already prototyped automated systems with robotic handling for writing and reading, and past proofs-of-concept have included etching entire movies like Warner Bros.' "Superman," preserving music in Arctic vaults through the Global Music Vault, and collaborating on a crowdsourced "Golden Record 2.0" to capture humanity's cultural diversity for future civilizations.

While the research phase of Project Silica concludes with these publications, Microsoft emphasizes that it continues to value the intellectual property and is exploring ways to apply these learnings to sustainable long-term digital preservation, potentially influencing cloud archival solutions or specialized enterprise storage.

This breakthrough arrives at a moment when organizations face mounting pressure to safeguard massive datasets, ranging from scientific records and cultural heritage to legal and corporate archives, against obsolescence and environmental risks.

By turning ordinary glass into a timeless vault, Microsoft offers a glimpse of storage that outlasts civilizations rather than merely years, blending cutting-edge optics, materials science, and machine intelligence into a deceptively simple yet revolutionary medium.