The AI boom has ushered in a new era of technological advancements, transforming the way people interact with machines and how companies compete in the digital space.

After OpenAI sparked an arms race with the release of ChatGPT, nearly every tech company—large and small—jumped on the bandwagon. Many began integrating Large Language Model-powered chatbots into their platforms, while others rushed to develop their own AI tools to stay competitive in this fast-moving landscape.

Apple, known for its deliberate and polished approach, eventually joined the movement. Though fashionably late, the tech giant unveiled its own AI initiative called Apple Intelligence in a bid to carve out its place in the generative AI space.

While Apple has always dabbled in AI through features like Siri and on-device machine learning, it had never taken such a bold step into generative AI. And when it finally did, things didn’t go entirely as planned.

Despite the hype, Apple Intelligence struggled to compete with existing AI models from rivals. It lacked the depth, flexibility, and user experience that other LLM-powered systems had already mastered.

The shortcomings were so noticeable that even Apple’s own researchers voiced skepticism, suggesting that Large Language Models aren’t nearly as "intelligent" as many people assume. According to them, these models often lack true reasoning and understanding, raising important questions about the future direction of AI development at Apple.

According to the researchers in a post on Apple's website:

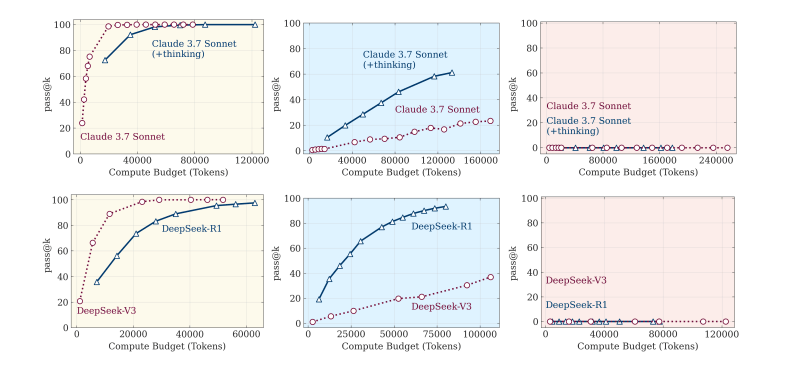

In the research, Apple evaluated five advanced reasoning models: o3-mini (medium and high configuration), DeepSeek's DeepSeek-R1, DeepSeek-R1-Qwen-32B, and Anthropic's Claude-3.7-Sonnet (thinking)—to see how they handle increasing problem complexity.

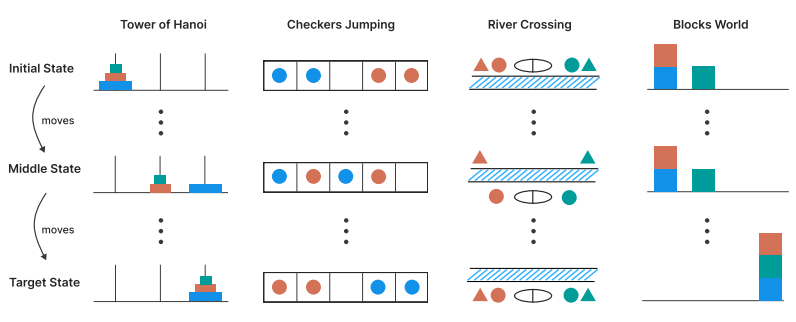

To deeply probe AI reasoning, Apple researchers designed custom puzzles (like Tower of Hanoi and River Crossing) with adjustable complexity. The idea is to pit Large Language Models (LLMs) and Large Reasoning Models (LRMs) to see where they excel at.

This approach avoids contamination from AI training data and lets them inspect not just outcomes but how the models reason.

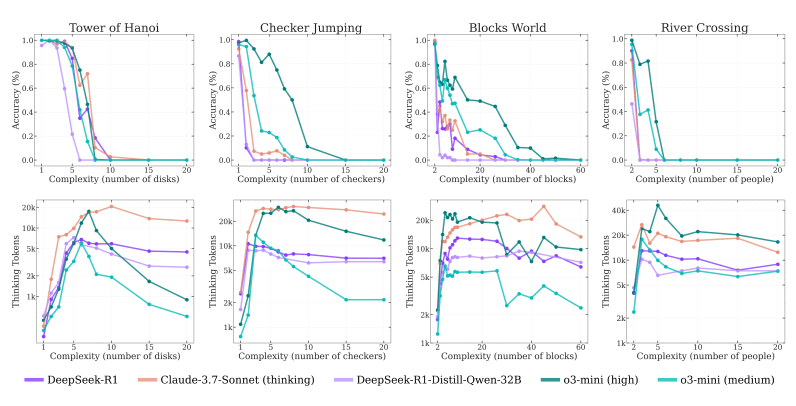

And here, the researchers identified three distinct behaviors as problem complexity grows :

- Low complexity: Standard LLMs (without reasoning prompts) sometimes outperform LRMs.

- Medium complexity: Thinking steps in LRMs yield better answers..

- High complexity: Both LLMs and LRMs collapse to near-zero accuracy..

The results revealed a consistent pattern across all models: as the problems got harder, accuracy steadily declined until it collapsed entirely at a certain threshold unique to each model.

The models initially increased their use of "thinking tokens" (inference effort) with growing complexity. But just before reaching their breaking point, they unexpectedly reduced this effort—even though they still had plenty of computational room left to "think." This behavior was most noticeable in o3-mini, and less so in Claude-3.7-Sonnet.

In other words, the models' accuracy drops to zero when puzzles exceed a certain complexity. And worse yet, LRMs actually think less on harder puzzles—even though they have token budget left.

Even when provided with explicit algorithms (e.g. steps to solve Tower of Hanoi), LRMs still fail above certain complexity.

Apple’s work highlights that:

- LRMs realize a partial gain, but only within limited problem complexity.

- Beyond that threshold, they fail sharply.

Apple concludes that this reflects a fundamental limitation: current reasoning models can’t scale their thinking effectively as problems become more complex, even when resources are available.

In essence, they hit a ceiling—and back off—right when deeper reasoning is needed most.

It's worth noting that the puzzle environments are controlled with fine-grained control over problem complexity. Apple said that the tests only "represent a narrow slice of reasoning tasks and may not capture the diversity of real-world or knowledge-intensive reasoning problems."

While Apple said that the tests do have limitations and may not represent real-life scenario, the findings raise questions, like do chain‑of‑thought models truly reason, or merely elaborate simulations?

Experts like Yann LeCun and Cassie Kozyrkov have long argued LLMs only "simulate intelligence" and that "they don’t think."

And Apple’s findings echo this, underscoring a need for hybrid architectures that combine symbolic logic, memory, and meta‑reasoning—beyond token prediction.