In what was meant to be a playful Halloween episode, one of Indonesia’s most prominent storytellers suddenly found herself at the center of an international storm.

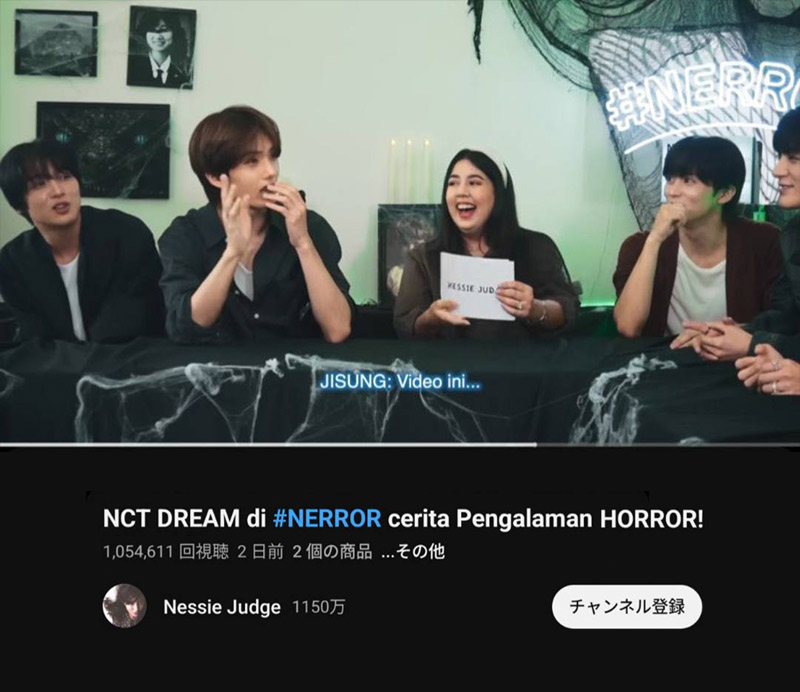

It all began when Nessie Judge, one of Indonesia’s biggest storytelling YouTubers, celebrated for her #NERROR true-crime and horror breakdowns followed by millions, released a special collaboration featuring the K-pop group NCT Dream.

At first glance, her "Spooktober" episode looked like any other production she had before: filmed in a familiar studio, wrapped in her usual blend of eerie fun and casual podcast-like approach. Everything appeared business as usual, until it wasn’t.

This time, Nessie wasn’t just entertaining her loyal Indonesian audience.

The appearance of NCT Dream drew a wave of international viewers, including many from Japan. What should have been a lighthearted crossover quickly turned sour when Japanese audiences noticed something deeply disturbing in the background: a single image that transformed a routine upload into a full-blown controversy.

Sharp-eyed viewers pointed out a framed photograph sitting quietly behind the hosts, a detail that might have gone unnoticed by most. But this was no ordinary photo. Japanese viewers immediately recognized the face in the photo.

And the person is that photo, is Junko Furuta, a teenage girl whose abduction, torture, and murder in 1988 remains one of Japan’s most horrifying and painful criminal cases.

To many Japanese viewers, seeing Junko’s photo used as a decorative backdrop in a Halloween-themed video wasn’t just careless. It was profoundly disrespectful. The realization spread like wildfire.

Within hours, outrage erupted across social media, and Nessie’s video became the center of an online firestorm that crossed borders and languages.

Soon after realizing what had happened, Nessie and her team acted quickly to take the video down.

But by then, it was too late.

Screenshots had already circulated widely, and the damage was done.

The issue began trending on X (formerly Twitter), picked up by international entertainment media, reviewed by other YouTubers, and sparked fierce debates among fans and critics alike.

In response, Nessie released multiple statements and public apologies, in Indonesian, English, and even Japanese, explaining that the inclusion of the photo had been an unintentional mistake, acknowledging what she called a grave lapse in judgment.

She explained that the photo’s inclusion was meant as an “homage” to cases frequently requested by viewers, not as a prop or decoration.

She expressed regret and promised to re-edit future content more carefully. Despite her efforts, the incident continued to haunt her reputation, serving as a stark reminder of how a single overlooked detail can spiral into a global controversy in a matter of hours.

But again, this wasn't just a matter of people getting "offended."

The abduction, torture, and murder of Junko Furuta stands as one of Japan's most infamous and harrowing crimes, emblematic of extreme human depravity. At just 17 years old, Junko became the victim of a prolonged ordeal that lasted over 40 days, filled with relentless physical and sexual violence, until her tragic death in early 1989.

Junko was a high school student from Misato, Saitama Prefecture, known for her good grades, part-time job, and avoidance of trouble.

On November 25, 1988, while cycling home from work, she was abducted by a group of four teenage boys led by Hiroshi Miyano, an 18-year-old with ties to the Yakuza (Japanese organized crime). The others were Jō Ogura (17), Shinji Minato (16), and Yasushi Watanabe (17). Miyano had initially approached her under the pretense of offering help after knocking her off her bike, but it quickly escalated into a kidnapping.

The boys took her to a house owned by Shinji's parents in Ayase, Adachi, Tokyo, where they confined her in an upstairs room.

Over the next few weeks, Junko endured unimaginable suffering.

She endured repeated rapes, with estimates exceeding 500 instances, perpetrated not only by her primary captors but also by additional accomplices the boys invited. The torture was relentless: beatings with golf clubs, dumbbells, and chains; cigarette and lighter burns; forced insertion of foreign objects, including a metal rod and a bottle; shaving of her pubic hair followed by burning her genital area; starvation combined with compelled ingestion of urine, feces, and insects; and prolonged exposure to extreme cold.

The beatings had disfigured her face, swelling it beyond recognition, while her festering wounds emitted a foul odor.

Her injuries, both external and internal, left her unable to walk, even to reach the downstairs toilet for basic needs. Confined to the site of her torment, to the point that the boys fed her only small amounts of food and eventually only milk, to which Junko languished in extreme weakness and severe malnourishment.

By this stage, the agony drove her to beg her captors to kill her and end her suffering.

.

The boys inflicted further psychological cruelty, forcing her to telephone her parents and falsely claim she had run away, thereby thwarting any search efforts.

Despite knowing of her presence, the Minato family, residing in the same home, chose not to intervene, allegedly due to fear of Hiroshi's yakuza connections.

By early January 1989, Junko's body could no longer withstand the abuse.

It was on January 4, after losing a mahjong game to her captors, she was beaten severely and doused with lighter fluid, which was set alight. She died later that day from shock, internal injuries, and burns.

She was 17 years old when she was murdered, just 14 days before her 18th birthday on January 18th.

The perpetrators then placed her body in a 55-gallon drum, filled it with concrete, and dumped it in a reclaimed land area in Kōtō, Tokyo.

Her remains weren't discovered until March 29, 1989, after an unrelated arrest of Miyano and Ogura for another gang rape led to a confession during police interrogation.

The case sparked outrage in Japan due to the brutality and the lenient sentences handed down. Because the boys were minors under Japanese law at the time, their identities were initially protected, though they were later revealed by media outlets.

Miyano received 20 years (the longest sentence), Ogura 5-10 years (released in 1999 but re-imprisoned for another murder in 2004), Minato 5-9 years, and Watanabe 5-7 years. All have since been released and attempted to reintegrate into society, with some changing names to avoid public scrutiny. The light punishments fueled debates on juvenile justice reform in Japan, leading to changes in how serious crimes by minors are handled.

The torture and murder of Junko Furuta has since been referred to as the "concrete-encased high school girl murder case," and has inspired books, films, and podcasts, serving as a stark reminder of unchecked violence and systemic failures. It continues to haunt public memory, underscoring the need for vigilance and justice.

Junko Furuta's name has been tied to a deep national trauma that still evokes grief and outrage.

Because of this, to many Japanese viewers, seeing her face appear casually in a Halloween-themed video was more than a cultural faux pas; it was an act of emotional desecration. What Nessie’s team may have viewed as an aesthetic choice came across as a tone-deaf trivialization of real horror. That context explains why the outrage was so fierce.

Many began calling for her cancellation, hurling harsh criticism and even issuing disturbing threats, with some going so far as to say that if Nessie ever visited Japan with her daughter, they would be made to suffer the same fate as Junko.

The backlash grew intense and deeply personal, with criticism coming not only from Japanese viewers but also from audiences across various countries, turning what began as a localized controversy into a global storm of condemnation.

However, the anger wasn't just about cancel culture for its own sake, but about respect for a victim whose story is sacred in Japan’s collective memory.

Many brushed off Nessie’s apologies, feeling that the justification only made things worse.

We’ve posted this, but genuinely, we never meant to upset anyone or worse, disrespect anyone, I truly do apologize. pic.twitter.com/EaKdCL5q62

— Nessie Judge (@nessiejudge) November 4, 2025

Thank you everyone for the feedbacks and corrections, this is very important to me and I learned a lot from this.

And I will keep this in mind moving forward. Once again, I am sorry.— Nessie Judge (@nessiejudge) November 4, 2025

To them, “homage” implied deliberate inclusion, and no amount of good intention could excuse the insensitivity.

Subsequent social posts, including one that hinted the video might eventually return after re-editing, further fueled distrust.

For her fans, the apology was heartfelt; for her critics, it was performative. And as Japanese and international netizens continued to dissect her every statement, the sense of outrage only deepened.

Hello, everyone. I have listened and understood your concerns regarding the previous video uploaded. What we recklessly thought as an act of paying an homage, was rightfully corrected by everyone as rude and insensitive. We deeply apologize for our severe lack of judgement.

— Nessie Judge (@nessiejudge) November 5, 2025

The backlash against Nessie Judge’s video took on a broader dimension, fueled in part by the historical reality that Indonesia was once occupied by Japan.

Between 1942 and 1945, during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, countless Indonesian women were subjected to the military’s system of sexual slavery, known as the "comfort women" (Jugun Ianfu) program. Women in villages were often deceived with false promises, coerced by local authorities, or outright abducted, then forced to provide sexual services to soldiers.

In cities such as Kupang, teenage girls were taken away from their families, placed in brothels, subjected to repeated sexual violence, and left with lasting physical and psychological scars. The system was highly organized: testimonies reveal systematic recruitment, classification, and deployment of women, including those already marginalized in society, all justified under the pretext of wartime necessity.

The controversy surrounding Nessie’s video also drew on an even wider historical consciousness.

Some commentators referenced other wartime atrocities committed by Japan, including the Nanjing Massacre of 1937-1938, when Japanese forces raped and killed tens of thousands of Chinese civilians. Such comparisons underscored that the outrage was not simply about a YouTube misstep, but about a broader pattern of historical trauma, exploitation, and violence across East and Southeast Asia.

Given this context, the use of imagery reminiscent of sexual violence or victimhood in modern media is deeply provocative.

When a prominent Indonesian content creator presents such imagery casually or decoratively, Japanese and international audiences may perceive it as more than insensitive: they see it as an affront to the memory of real suffering. The anger reflects not only cultural disrespect but also a resonance with regional historical trauma, connecting the exploitation of Indonesian women during the occupation with the enduring memory of atrocities in Japan and beyond.

We deeply apologize to the victim, to the victim’s families, to our viewers and collaborators, and to everyone. While it was never our intention to cause harm, I understand that the impact of our action is far more important. Thank you for reminding us and holding us accountable.

— Nessie Judge (@nessiejudge) November 5, 2025

Yet this controversy didn’t emerge in isolation.

Nessie’s content style, which is polished, cinematic retellings of true-crime stories and online folklore, has always occupied a gray ethical space.

Over the years, she has faced accusations of lifting stories or social-media threads without properly crediting their original authors. Such claims, which once faded quietly, resurfaced with renewed force after the Junko Furuta backlash.

To critics, this incident was the latest proof that Nessie’s storytelling blurred the line between tribute and exploitation, between empathy and opportunism.

What had once been brushed off as creative liberty was now being reframed as a pattern of insensitivity, built on borrowed pain.

Ultimately, this saga reveals an uncomfortable truth about digital fame.

Online fame can bring both influence and fortune, but also real accountability, where both intent and consequence fall into the same unforgiving spotlight.